On the 8:27 a.m. slow from Dadar to Churchgate, Shantilal Biswas stood in the doorway like a well-behaved sardine. He was middle-aged in the sincerest possible way—forty-seven going on “beta, you just focus on your job.” His belly was not a belly so much as a polite suggestion of one. His hairline had retreated respectfully, like a gentleman yielding a seat to a senior citizen. He wore the uniform of his tribe: office shirt in a shade of blue the Pantone catalogue might call “GST Filing,” and trousers whose creases had survived the monsoon solely through stubbornness.

He was thinking, as he did most mornings, of the Grand List.

The Grand List had twenty-three items. It lived in the Notes app and in an increasingly superstitious corner of his brain. “Points of Inflection,” he called them, because he’d read a LinkedIn article once. If he could change just one, his life—he believed with the evangelical certainty of an uncle who’d just discovered kombucha—would have turned out spectacularly different.

There was the big one: Bulbuli. “Call her back in ’99 when she rang from the PCO.” There was the stock market one: “Put 50k in Titan in 2002—NO SELLING.” There was the real estate one: “Buy a kholi at a Lower Parel chawl when Mausi said, don’t be a fool, let it go.” And the smallish-but-actually-big one: “Don’t fight with Anjali about the ‘useless’ food processor; apologize.” (He had apologized eventually, but late apologies, like late trains, arrive with too many explanations.)

Shantilal clutched his lunchbox—aloo posto with a seditious green chilli—and sighed. The train lurched into Churchgate, and life, like a borewell, kept droning.

***

Bhooter Raja arrived in the most respectable way a ghost can: inside the lift of a BMC building, exactly between the fourth and fifth floors. One moment Shantilal was alone, the next he was accompanied by a gentleman in a cream dhoti and a blazer that had strong opinions about shoulder pads. The gentleman’s moustache curled at the ends like quotation marks around a punchline.

“Nomoshkar,” said the gentleman. “I am the King of Ghosts. In this building, at least. The bigger king handles South Bombay; he has a union.”

Shantilal stared at the lift pane. It reflected two men: one regally spectral, one stubbornly corporeal. The spectral one adjusted his blazer and sniffed. “Tell me, Shontilal—”

“Shan-ti-lal,” said Shantilal, by reflex.

“—Shan-ti-lal, why is your face like a rejected brinjal?”

“I was thinking,” said Shantilal, “if only I could change one thing… my life would be… different.” He didn’t say “better.” He was Bengali in Mumbai; the word better had to be negotiated like a rent increase.

“Arre, toh bolo,” said Bhooter Raja kindly, as if granting a turn in antakshari. “Today is your lucky day. I grant you one boon: change one thing from your past. One. Thing. See how it changes your future.”

“Anything?”

“Anything,” said the King. “Except the outcome of India-Pakistan matches. That department has its own heavenly committee. Very political.”

The lift gave a token shudder, like an old aunt disapproving of mixed marriages. A light flickered. Shantilal’s heart banged the grill.

He should have said, “Call Bulbuli back.” He should have said, “Buy that 1BHK in Lower Parel.” He should have said, “Tell Baba I forgive him.”

But the Grand List, in its entirety, absconded from his head. Blank. The way your mind goes smooth as a dosa pan just when someone says, “Name five countries in Africa.” In that sizzling panic, Shantilal’s tongue, which had never been under his control, reached blindly into the attic of his memory and pulled out something small, dusty, and ridiculous.

“Okay,” he blurted, “I will change my first email ID.”

Even the lift stopped humming out of surprise.

“Your what?” said Bhooter Raja.

“My first email ID,” said Shantilal, sweating. “At the Sify cybercafé in 2003. Instead of ‘shantilal_b@rediffmail.com’ I will make it ‘shanti.lal@rediffmail.com.’ One dot. That’s all.”

The King blinked, then smiled with dangerous benevolence. “One dot? Shobcheye chhoto payra o kotha niye ashe. Even the smallest pigeon brings news.”

He snapped his fingers.

The lift hiccupped.

The doors opened.

And Shantilal stepped into a hallway that smelled faintly of lemongrass and improbable destiny.

***

The first thing he noticed was his shoes. They were not shoes; they were curated experiences for his feet. The second thing he noticed was a brass nameplate on an apartment door that said “Shanti Lal, Wellness Architect.” Underneath, in smaller letters, “(formerly Shantilal Biswas).”

Inside his own house (which, thankfully, was still Anjali’s house too— thank you, Boroline), a bamboo plant leaned in a corner like a diligent intern. There were yoga mats rolled up like the future. There were low cushions that said “Breathe” in fonts that had gone to private school. The old Godrej almirah had been painted a rebellious teal.

And there was Anjali, in linen, looking suspiciously radiant. “Guruji,” she said, teasingly, then rolled her eyes. “Come in. Some TV people called. Again. And your students from the ‘Mindful Mondays for Mid-Managers’ cohort want to shift their session because of naag panchami.”

“Guruji?” said Shantilal.

Anjali grinned. “You’re trending again. Someone cut together all your ‘Drink water first, then panic’ clips. It’s a proper reel. You’re famous in Thane now.”

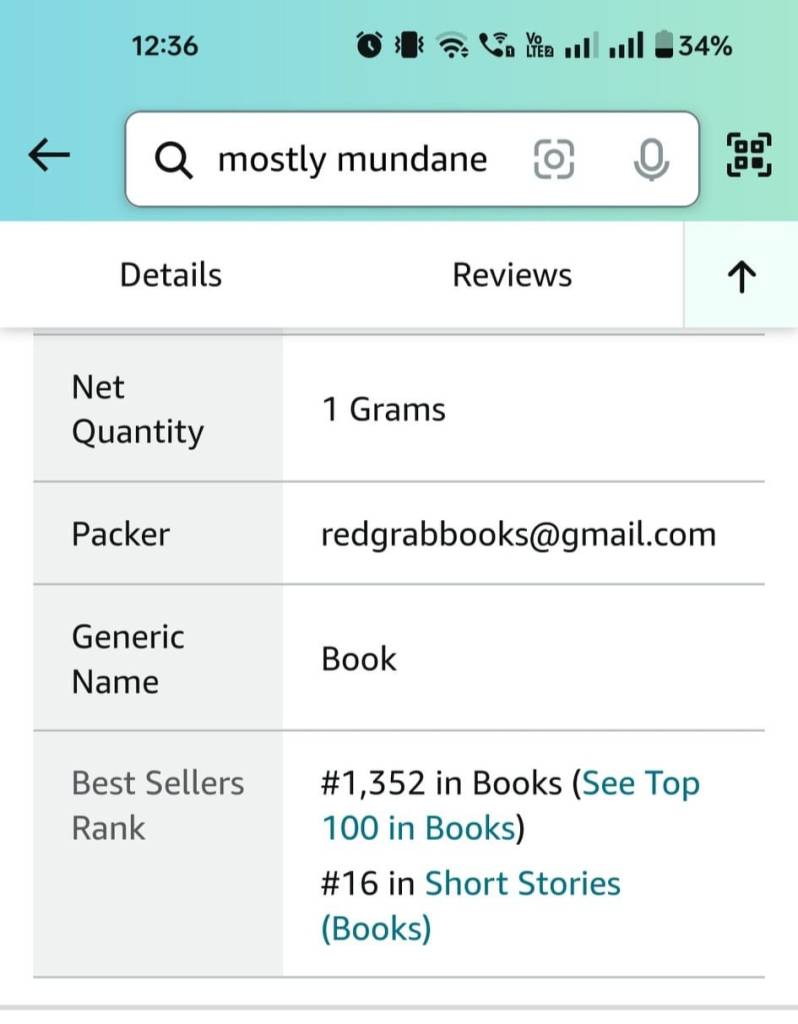

He sat down gently, like he’d been rented. On the centre table was a copy of a glossy magazine: Corporate Calm. The cover star was him, eyes closed mid-breath, captioned “SHANTI LAL: HOW ONE EMAIL CHANGED MY LIFE.”

He read like a man who had found a mirror he didn’t apply for.

“Once an auditor at a government project office, Shanti Lal is now the Wellness Architect Fortune 200 leaders call when their backs hurt from spreadsheets,” the article announced. “His signature method—Five-Minute Shanti—combines breath, Bengali common sense, and a prodigious mastery of WhatsApp groups. He discovered his vocation by accident in 2006, when an invitation for the revered meditation teacher Shanti Lal was misdirected to his email: shanti.lal@rediffmail.com. He attended the event to explain the mix-up, accidentally took the stage, and told 200 stressed sales executives to (quote) ‘chew slower and stop forwarding nonsense.’ The video went viral before viral was a thing. The rest is self-care history.”

Shantilal looked up. Anjali watched him with the fond exasperation of someone who had ironed his kurtas for TEDx. “You still get stage fright,” she said. “In a very adorable way. You say ‘folks’ too much. Your followers think it’s your mantra.”

He tried to inhale the new air and coughed on success. “Where’s my tiffin box?”

“Guruji,” said Anjali, “your 12:30 is a CFO who had a meltdown because his Excel autosaved in the wrong folder. You’ll be fine. Just watch out for the ‘alpha breathers’—they try to out-inhale you.”

He staggered into the bedroom. On the wall were framed photographs of him sitting on unforgiving floors with very forgiving smiles, flanked by people whose job titles were longer than their lunch breaks. In one, he stood with an IPL team owner, both holding a giant water bottle like a trophy. In another, he was at a Ganesha pandal, teaching aunties how to do neck rotations without knocking over modaks. In all, his shoulders were relaxed in a way his old shoulders had only read about.

His phone pinged: “Namaste Guruji, quick tip for in-laws coming for ten days? – Rajeev.” Another ping: “Can you bless our new office ergonomic chairs?” – Sneha (HR)

He checked WhatsApp. He had three groups named Shanti Squad (one with the ‘™’ sign). He had fan art of himself sitting cross-legged atop a Mumbai local, like a deity of punctuality.

He went to the balcony. Mumbai was the same: insistent and golden, a city that could make a melody out of horns. Somewhere, a pressure cooker sang. Somewhere, a dog debated a crow. Somewhere, a child said, “Mummy, I did not hit him, I only touched his face swiftly.”

He closed his eyes. A memory arrived like an auto in rain: uninvited and miraculous.

Sify cyber café, 2003. Fans rattling like gossip. The first time he made an email ID. He had typed “shantilal_b,” but the session crashed. He had typed “shanti.lal” just to try a dot. The dot had, in this timeline, opened a portal.

And because of that dot, in 2006, the invitation meant for a meditating saint had landed in his inbox. He had gone to apologize in person. Someone had assumed he was the guru. He had gone on stage to correct the misunderstanding. Someone had clipped on the mic. He had panicked and said, “Folks, first drink water.” Two hundred men had obediently sipped. And the universe, moved by his nonsense, had decided to be generous.

A dot. Beta, a dot.

“Baba!” called out a voice that had—to his knowledge, in his previous life—no business existing. He turned. There stood a boy of sixteen with his eyes and Anjali’s nose, backpack slung, speaking in a mouthful of city. “I’m going to Harkat for poetry open mic. Don’t give me tips on breathing while reading. We’re going to perform and then not get into anyone’s car, because safety.”

“Uh,” said Shantilal.

Anjali came to stand beside him. “I told you we had him,” she said, reading his face. “Monty. You forgot, Guruji? Your memory is like Vodafone in a tunnel.”

Monty rolled her eyes while stuffing earphones into a pocket already full of bakery receipts. “Baba, you’re trending for saying ‘the office is also a body,’ by the way. My friend wrote an essay. Can I borrow your black kurta? I’m doing a piece on fathers who alphabetize their spice racks.”

“I don’t alphabetize,” said Shantilal, wounded. “It’s by pungency.”

Anjali snorted. “Go. Bless some spreadsheets. Try not to tell anyone to hydrate an Excel file.”

***

He went to South Bombay in an Ola whose driver insisted Shahrukh once sat exactly there, and fate is in seatbelts. The CFO awaiting him in a glass box had the pallor of a man who’d been personally betrayed by pivot tables. Shantilal sat, crossed his limbs with the gravitas of someone who’d learned it from YouTube, and said, “Folks—” to one person “—first drink water.”

The CFO obliged. Then he began to speak.

“Your file has a history of saving in the wrong place,” Shantilal said, in his domain—absurd advice distilled into compassion. “You have a history of saving yourself in the wrong place. When the file does this, it is crying. So are you. Make a folder called ‘I Deserve Better.’ Put everything there. Later, make another called ‘Archive My Pain.’ Put everything there. Then tell your boss you need a quiet room between two and four, or I will come and do yoga here and make corporate history.”

The man nodded, tears breeding constitutional rights in his eyes.

It turned out to be the easiest thing in the world—to say simple sentences with your whole body. People mistook it for wisdom. People tipped.

By late afternoon, he had blessed four chairs, three managers, and a refrigerator. He had said, “Take a breath” twelve times and meant it at least eight.

Back home, Anjali put a bowl of muri on the table. “Remember Bulbuli?” she said, casually, as if dropping a century into a teacup.

He froze.

“Of course,” he lied. “I always… remember… Bulbuli.”

“She messaged your shantilal_b address,” said Anjali, not looking up. “The one you never check now. There’s a reunion. She said she’s bringing her son.”

A bruise bloomed on a part of him he had pretended did not exist. The Grand List ghosted him with a spiky laugh.

“Do you—” he cleared his throat, which had suddenly turned into Juhu beach. “Do you mind if I…”

“Go,” said Anjali. “Wear the blue shirt. Take the black umbrella. Don’t propose to anybody.”

He leaned down, kissed her forehead like it owed him money. “You’re—”

“—the one who found your email password when you forgot it,” said Anjali. “I know.”

***

On the way to the reunion, Mumbai rained like it had misread the script and was overacting. Shantilal stood under the awning of a bakery, chewing a sugar-dusted bun and waiting for the downpour to downgrade itself. As he watched, two college boys in one shared umbrella passed by, their laughter bouncing off puddles like rubber balls. The city contained so much life; you could never finish the whole plate.

At the hall—rented sentiment and perfumed nostalgia—there were name tags, paper cups, and people making small talk with the ferocity of war correspondents. He found Bulbuli by the comfortable slope of her shoulders. She turned; time, that lousy editor, had left the best parts uncut. Her eyes did that thing Kolkata girls’ eyes do when they recognize an old friend and an old absurdity in the same person.

“Shanti,” she said.

“Bu” He coughed. “Bulbuli.”

“You look…” she began, then surrendered. “You look like you have a new email ID.”

They sat, two people who had once been a unit of chaos. They spoke of the years like reviewers. She worked at a public library now, she said, teaching boys who thought Macbeth was a footballer to love sentences. She had a son whose hair was a conspiracy against combs. She had a laugh that hadn’t retired.

“I called you from a PCO, remember?” she said, softly. “In ‘99. You didn’t call back.”

“I meant to,” he said, and was surprised to hear the truth come out on its own two feet. “It was on my list.”

“List?”

“Points of inflection,” he said. “A fancy way of saying ‘regrets I have curated.’”

She smiled at the ridiculous things he had always said. “Well,” she said, “you look… content.”

He thought of Anjali alphabetizing pungency, of Monty demanding a kurta, of CFOs discovering their lungs. He thought of the dot. It felt like an accident that had chosen to be kind.

“I am,” he said. “In such a funny way.”

A silence sat between them—pleasant, plucked, inevitable. They were not a story anymore; they were an anecdote in each other’s biographies. Outside, rain took a smoke break.

“Here,” she said, taking a small book from her bag. “My favourite Tagore lines. I keep a copy for friends I didn’t marry.”

He took it like a blessing. On the title page she’d written: “Faith is the bird that feels the light…” He smiled. Of course.

They hugged the careful hug of people who had made different good mistakes. Then she was gone, trailing an unfashionable grace.

He stood in the hall until someone told him to stop blocking the snacks. He went home with a book and an appetite and a sense that the universe had shoved him gently into the correct lane.

***

At night, in the kitchen, he found the Grand List, wobbly and transposed by events. He took a pencil and wrote: “Item #0: One dot.”

Anjali leaned against the counter, watching him with that look—half accomplice, half immigration officer. “So?” she said.

“She’s happy,” he said. “I am, too.”

“Good,” said Anjali. “Happiness is like Hilsa. Seasonal, slippery, and the bones can hurt, but you keep chewing.”

He laughed. “Will you allow me to be unbearable for a moment?”

She sighed theatrically. “Proceed, Guruji.”

He raised the pencil like a baton. “Maybe the point of inflection is not the height of the cliff but the angle of your head.”

Anjali stared. “Take out the trash.”

***

Weeks passed in a montage only Mumbai could choreograph- trains that flirted with chaos, samosas that healed generational trauma, elevators that negotiated with gods. Shantilal blessed offices like a priest of the spreadsheet. He taught breath to people who wanted promotions. He told one man to resign and rest for two months; the man returned with a face that had remembered it was human.

He learned new things about fame. That it arrives like a stray dog—hungry, lovable, and requiring you to rearrange your life. That people will project onto you; they will put their fear in your pocket because you look like you have zip. That it is possible to be both guru and fool, and on most days the fool has better jokes.

He also learned to read his inbox.

He found, in the dusty back alleys of his shantilal_b account, a thousand almosts. Spam from a decade. A thread where a stranger had sent him a kind paragraph when he was not yet the sort of man who received such things. A message from a long-ago manager: “I was rude. Sorry.” A chain of invitations for someone else entirely, which had, in this timeline, rerouted the river of his life.

A dot. Beta, a dot.

He replied to one: “Dear Sir, apology accepted. We were all sharp then; now we try to be round.”

He wrote to another: “Thank you for the kind paragraph from 2012. It took the scenic route. It has arrived.”

He sent Bulbuli a photo from inside the public library he had visited on a whim one afternoon, a row of boys reading like a plot twist. “Your empire,” he wrote. She replied with a sticker of a dancing fish.

In his sessions, he started telling the story of the dot. Not as a sermon, but as a convenience. People needed metaphors that could travel economy class. “Your dot,” he would say, “might be a comma you put after your name. It might be the day you answered a phone call. It might be the shut-up you did not say. Choose small and honest; the big things come dressed in little clothes.”

They listened. Sometimes they cried. Sometimes they asked if they should buy gold. He said he was not that kind of guru.

***

One evening, the lift stalled again. Shantilal smiled into the mirror. He did not panic. He had snacks. He had bars of peanut chikki the way survivalists have solar panels.

The air went wobbly. The King of Ghosts stepped into focus, blazer still producing shoulder opinions.

“How’s the dot?” asked Bhooter Raja, as if inquiring after a child.

“Powerful,” said Shantilal. “Unemployed men of Worli breathe at me in the evenings.”

“Very good,” said the King. “You chose a small hinge. The door was large.”

Shantilal looked at his face—the same, mostly. Some parts softer, some parts sharpened by being useful. “I had a list,” he said. “Things I would change if I could. I forgot the list.”

“Sometimes forgetting is the boon,” said Bhooter Raja, patting his moustache. “Had you remembered, you would have chosen drama. Drama gives you applause. Dots give you a life.”

Shantilal nodded, then chuckled. “There is one small problem, though, O King.”

“Bolo.”

“Because of the email ID, people keep spelling my name as Shanti Lal—two words. In bank forms. In KYC. Even Excel. The registry office called me First Name: Shanti Last Name: Lal. Our neighbour calls me ‘Lalu.’”

The King laughed the laugh of men who have eaten wedding biryani on rooftops. “Aha. The universe is not a typo-free zone.”

“What do I do?” said Shantilal. “Change it back?”

The King considered, then shook his head. “Naa. Keep it. A little confusion is good for the ego. Also, Lalu is a strong name.”

They grinned at each other, the man and the memory. The lift resumed its opinion about friction.

At the door, before the ghost dissolved, Shantilal said, “One more boon?”

“Arre, boom-boom,” said the King, indulgent as a Bengali uncle at a rice festival. “You have become greedy, Guruji. But ask.”

“I want to remember,” said Shantilal, surprising himself, “to keep my present as my main subject.”

The King smiled in a way that made the tube light look lyrical. “Approved,” he said. “No take-backs.”

And then he was gone, as kings often are when the punchline has landed.

***

On a Sunday that smelled of frying and damp newspapers, Shantilal, Anjali, and Monty sat on the floor, playing carrom with the seriousness of diplomats. Between thumb flicks, Monty performed lines from his poem-in-progress (“Fathers who fold T-shirts like apologies”), Anjali heckled (“Make it ‘Fathers who fold badly like apologies’”), and Shantilal engineered shots like a man who believed geometry owed him money.

“I wrote something,” said Monty, sliding a scrap of paper across to him when Anjali went to rescue an appam from the pan. “You can use it in your sessions if you want. Or not.”

He read. It said:

“At the heart of a city is a tiny dot,

a kiosk where the life you meant to live

accidentally forwards to you.

You open it.

You reply all.”

He stared at his son. “This is… khub bhalo,” he said quietly. “It will make grown men in glass offices leak.”

“I know,” said Monty, with imperial confidence. “Also, can I have money for an Uber?”

“Take the train,” he and Anjali said together, then laughed so hard the striker skittered under the sofa and refused to come out.

After lunch, when the city performed its siesta like a tradition, he settled by the window with Tagore’s lines and a cup of suspiciously expensive tea. He wrote another list—not of inflections, but of dot-sized practices.

- “First drink water.”

- “Breathe before pressing send.”

- “Don’t sort people by pungency; keep that for spices.”

- “Say sorry in the same decade.”

- “Learn one new Marathi joke for auto drivers.”

- “Bless chairs only upon request.”

He looked out. A kite hung in the sky like punctuation. Children argued about whose cricket ball it was. Somewhere a pressure cooker’s second whistle declared the end of world wars.

Shantilal closed his eyes—not like a guru, not like a cartoon, but like a man who had found a bench in a crowded station and sat, not caring who thought he looked foolish. He remembered Baba’s hands, cracked like good pottery. He remembered his mother’s way of turning grief into food. He remembered Bulbuli’s laughter as a path he did not take but was glad existed. He remembered Anjali, steady as a hand on a head feverish with ambition. He remembered Monty’s poem.

He opened his eyes with the simple responsibility of a man with an inbox.

There would be clients who believed breathing was a scam. There would be trolls who said, “Shanti, please also fix my wife.” There would be bank forms calling him Lalu. There would be evenings when he wondered about the undiscovered chawl in Lower Parel, the portfolio he never had, the version of himself who called the PCO back. He would wave at those ghosts and proceed to soak moong.

The dot had done its job. The rest was practice.

At 7 p.m., on the slow train, in the doorway where gods stand, he leaned out just enough to feel the wind turn his face into a sail. He smiled at nothing. He tipped his head toward a little girl who was not supposed to be standing at the door but was, on balance, doing it like an expert. “Beta,” he said gently, “first step back, then see the view.”

She obeyed. The city flowed past, unembarrassed by its own brilliance.

Somewhere between Lower Parel and Elphinstone, a ghost king in a cream dhoti adjusted his blazer with pride. Somewhere, a CFO told his boss, “Two to four is my quiet room; please email.” Somewhere, a poet read a line that made a room exhale.

And in a tiny corner of the internet, the dot that had once been the whole story blinked like a traffic light saying: now go; you have thought enough.

“Folks,” said Shantilal, to the compartment or to the universe, who knew, “first drink water.”

He did.

And then he laughed, loudly enough that even the train had to smile.