After a brief Amazonian adventure (blame the Great Indian Festival, not us!), Mostly Mundane is NOW AVAILABLE!

Grab your copy before it disappears again! (Just kidding…we hope!)

After a brief Amazonian adventure (blame the Great Indian Festival, not us!), Mostly Mundane is NOW AVAILABLE!

Grab your copy before it disappears again! (Just kidding…we hope!)

The scene opens in Saugata’s cramped study, the air thick with the scent of panic and stale coffee. Saugata, a nervous wreck, is pacing back and forth, his phone clutched in a death grip. Shantilal, the picture of nonchalance, is sprawled on the lone armchair, his feet propped on a teetering pile of manuscript pages.

“Shantilal, this is a disaster!” Saugata wails, his voice reaching an octave that would make a soprano jealous. “The book is out there, but it’s not out there! It’s like a literary Schrödinger’s cat!”

Shantilal yawns, unperturbed. “Yes, yes, I have seen the Hans India today. They have put it up on their Bookshelf. I thought good press on the day of release was what would make you happy.”

Saugata raises his head, his eyes bloodshot. “Shantilal, have you seen Amazon? The book’s not there! People are asking, and all that I can say is that’s the missing link!”

Shantilal chuckles, reaching for a half-eaten samosa on the desk. “Saugata, my friend, relax. A little chaos is good for the soul, and excellent for book sales.”

“Chaos? This is beyond chaos! It’s like we’ve launched a rocket without the fuel!” Saugata sputters, his voice reaching a fever pitch. “And it’s all thanks to that blasted Great Indian Festival on Amazon! They’ve delayed the release, and now we’re stuck in limbo!”

Shantilal leans back in his chair, steepling his fingers. “Think of it as a treasure hunt, Saugata. The readers are the intrepid explorers, and your book is the elusive prize. Besides, a little delay might just build up the anticipation.”

“Explorers? They want to buy the book, not scale Mount Everest to find it!” Saugata explodes, stopping on his tracks. “And anticipation? More like frustration! We’re losing sales to that festival frenzy!”

“Patience, my friend,” Shantilal says calmly. “Remember, you only have made me write that the greatest successes are often born from the most chaotic beginnings. Even Amazon’s festival will end, and then ‘Mostly Mundane’ will have its moment in the sun.” He adds with a wink, “Besides, haven’t you always said you wanted your book to be ‘Mostly Mundane’, but its launch to be anything but?”

Saugata pauses, a reluctant smile tugging at his lips. “You have a point there, Shantilal. But next time, can we aim for ‘Mostly Mundane’ in all aspects, including the launch?”

Shantilal chuckles. “Where’s the fun in that, Saugata? Now is the time to embrace the chaos. It’s where the magic happens. And who knows, this Amazon delay might just turn out to be the best marketing strategy we never planned.”

[SCENE START]

INT. A BOOKSTORE – DAY

Saugata is frantically pacing while Shantilal, looking dishevelled as ever, leans nonchalantly on a bookshelf.

SAUGATA:

(Waving his arms) The 15th?! But that’s barely enough time to alert my legions of adoring fans!

Shantilal! This is madness! Utter, complete, absolute madness!

SHANTILAL:

(Raises an eyebrow) Oh, do calm down, my dear Saugata. A little chaos adds spice to life, wouldn’t you agree?

SAUGATA:

(Throws his hands up) Spice?! The release date for ‘Mostly Mundane’ has been moved up two weeks! We’re talking about a seismic shift in the literary landscape! I haven’t even finished polishing my acceptance speech for the inevitable literary awards and you’re talking about spice? SPICE!

SHANTILAL:

(Smooths his moustache) Ah, but isn’t a seismic shift just a grander form of spice? A bit more… potent, perhaps.

SAUGATA:

(Stares incredulously) You… you are unbelievable.

Just then, Suhail, the famous literary agent, enters, looking slightly flustered.

SUHAIL:

What on earth is going on here, Bro? I hear talk of seismic shifts and potent spice…

SAUGATA:

(Turns to Suhail with relief) Oh, thank goodness you’re here! Shantilal seems to think this whole release date fiasco is a minor inconvenience!

SHANTILAL:

(Chuckles) My dear Saugata, you mustn’t fret. The world is eagerly awaiting the chronicles of my exploits. A little change in schedule only heightens the anticipation.

SAUGATA:

(Sighs) Shantilal, while I appreciate your optimism, we have marketing plans, bookstore arrangements…

SHANTILAL:

(Waves a dismissive hand) Details, my friend, mere details. Leave those to the capable hands of Suhail here. I’m certain he’ll navigate this minor turbulence with his usual aplomb.

Shantilal winks at Suhail, then turns and strolls away, whistling a jaunty tune.

SAUGATA:

(Shakes his head) Sometimes, I swear, that man exists solely to test my sanity.

SUHAIL:

(Pats Saugata on the back) Come on, let’s go grab a coffee. And then we’ll figure out how to handle this… seismic shift.

Suhail and Saugata exit for the bookstore cafe, leaving behind a trail of bewildered laughter.

[SCENE END]

[Curtains]

The audit gods continued their mischievous streak with Shantilal. Ink was barely dry on his Muchipara report when a new assignment landed on his desk. This time, fate deposited him in the sleepy town of Dinnaguri in North Bengal, a place famed for its royal palace, its lush green stretches, and a lingering suspicion that the laws of nature bent slightly within its borders.

Shantilal was no stranger to the quirks of small towns, but Dinnaguri was in a league of its own. The designated guest house was a former colonial bungalow, complete with faded portraits of stiff-necked Englishmen that seemed to follow his every move. The first night was an assault on the senses. A raucous frog concert erupted in the overgrown garden, a family of rats squabbled enthusiastically in the ceiling, and a ceiling fan with the ominous wobble of a helicopter about to crash kept him wide awake.

The morning offered little improvement. Dust whirls were a particular Dinnaguri spectacle, locals called them ‘djinns’ – playful spirits with a penchant for wreaking havoc. Shantilal was tasked with auditing the local college’s use of an obscure scholarship fund, and the rambling explanations of the principal had him chewing the end of his pencil into a nervous pulp.

Seeking respite, Shantilal escaped for a walk that afternoon. It was then fate, with its usual disregard for Shantilal’s sanity, intervened. A dust djinn, like a swirling dervish, was heading straight down the road, scattering papers and panicked chickens in its wake. And charging right into its path was a young woman. She was clad in a vibrant sari, her long braid flying out behind her. Plunging straight into the heart of the swirling dust, she vanished for a moment, only to reappear a few steps later clutching a sheaf of what looked like exam papers.

“Silly thing,” she said to herself, tucking the recovered paper into her bag.

Shantilal, utterly baffled yet oddly charmed, found his voice. “That… that was quite dangerous!”

She regarded him with calm amusement. “It wouldn’t be the first time I chased down a runaway exam thanks to these djinns. Children will be children, even when they are made of dust.”

“You… you teach?” He blinked, the image of her fearlessly battling a dust whirl seared into his brain.

“Higher Secondary. English and History.” Her eyes sparkled. “My name’s Anjali.”

Thus began the most peculiar interlude of Shantilal’s life. There were hurried walks between classes, shared cups of tea on a rickety tea-stall bench, and halting conversations that navigated Anjali’s gentle laughter, and Shantilal’s fumbling attempts to decipher the local dialect. He discovered that Anjali was as fierce in the classroom as she was when battling dust whirls, with a passion for literature and an iron will that seemed at odds with her petite frame. His audit became a backdrop to these rendezvous. In Anjali, he found a counterpoint to his ledgers and lists. She taught him to see the town beyond its dusty façade – its vibrant markets, the crumbling remnants of an old fort, the unexpected beauty of sunsets over the tea gardens.

All too soon, his assignment ended. It was time to pack up his ledgers, thermos, and mosquito coils. On his last day, Anjali walked with him to the run-down bus station. There were no grand declarations of affection, no promises etched in stone. Just two shy smiles and a touch of lingering warmth where their hands brushed as she helped him with his eternally battered briefcase.

As the bus rattled away, Shantilal stared out at the blurring green landscape and felt an emotion he hadn’t in years: hope. It was a fluttery, absurd thing, as delicate and unexpected as a butterfly in a ledger book.

Routine tried to reclaim him in Calcutta. But it found him distracted, his curries bland, his ledgers curiously less engaging. Then, one Tuesday, an envelope arrived from Dinnaguri. Its contents? A letter from Anjali, written in a flowing hand. She mentioned an opening for an Accountant, a desperately needed administrative position at the District Inspectorate of Schools. And a subtle hint – wouldn’t a man of his meticulous nature be an asset to their little town?

Shantilal, accountant and accidental romantic, smiled for the first time in weeks. It seemed Dinnaguri, with its djinns, its defiant schoolteacher, and its strangely enchanting chaos, wasn’t quite done with him yet.

(Note: Dinnaguri, like Malgudi can’t be find on the map. That doesn’t mean the rest of the story is imaginary. In ‘Mostly Mundane’, you shall find Shanti and Anjali, years later, in the maximum city of Mumbai. Their journey from Dinnaguri to Mumbai is yet to be chronicled.)

Is your daily grind feeling like a rerun of yesterday’s to-do list? Does the thought of folding laundry make you yearn for a meteor shower? Fear not, weary traveller of the ordinary! Mostly Mundane is here (well, not yet) to inject a shot of laughter into your life that’s stronger than your morning coffee.

This book doesn’t preach about productivity or finding your Zen. It reveals the hilarity hidden in the seemingly mundane aspects of daily life.

From an epic hunt for organic veggies to the existential dread of the never-ending parent-teacher meetings, Mostly Mundane transforms the ordinary into side-splitting adventures. Get ready to laugh out loud and emerge with a fresh perspective that will leave you chuckling at the world- and yourself- in a whole new way (as Tagore on the wall does here)!

[Note: Mostly Mundane is an eagerly awaited {no tall claims there, the author is waiting for it with fish eyes (that is without blinking)} book of 19 odd (without the hyphen, the oddity stands out) slice of life stories from the life of Shantilal and Anjali. The next post in the site would feature the story of their first meeting that got it all started.]

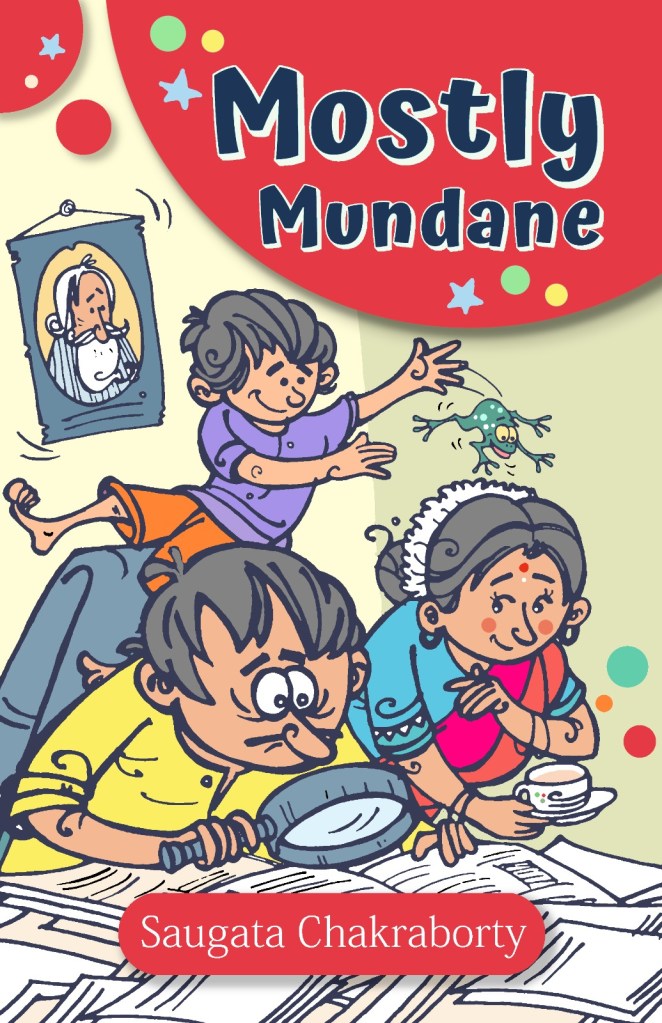

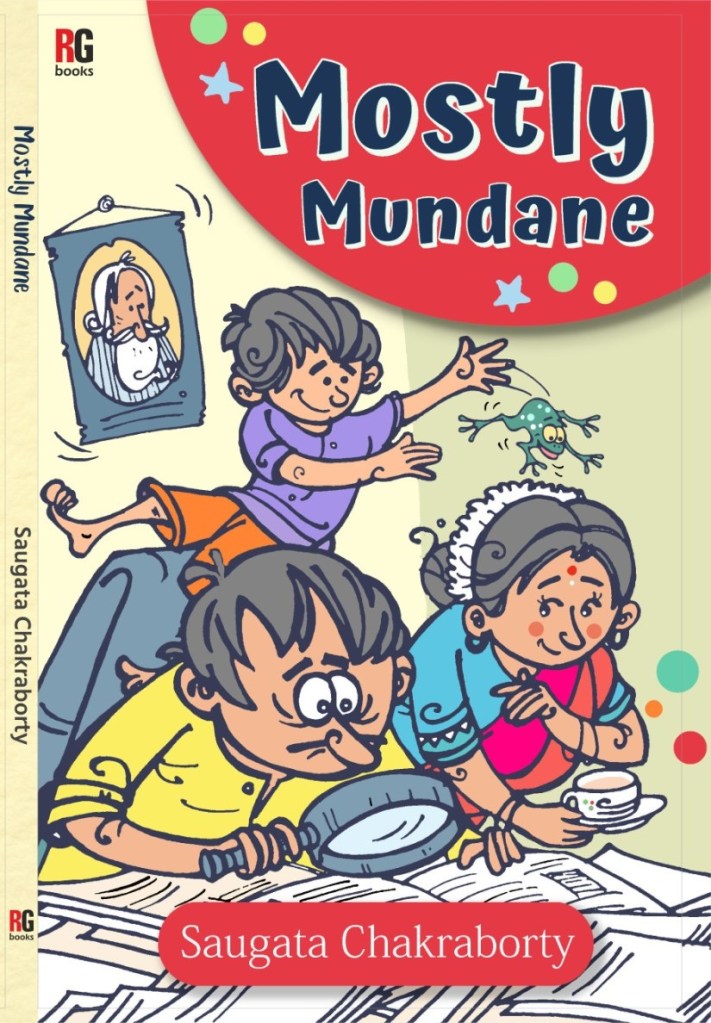

“I would like you to work on the cover of my new book. It’s a humorous account of the life of one Shantilal Biswas, who frequents those facets of life where neither shanti (peace) nor biswas (trust) resides. Shanti and Anjali live in a Mumbai suburb with their 12-year old son Monty (the Mischievous). Would you be interested in doing the work?”

From that first query to this first “rough sketch” for the cover sent over WhatsApp, the three-week journey had only one pit stop- prompt for the cover. It went like this:

“Cartoon illustration of Shantilal’s family in their suburban Mumbai flat. Monty is seen holding a frog in both his hands, ready to release it on Anjali’s head. She is seen wearing a saree with flowers in her hair bun, carrying a cup of tea to Shanti, who is poring over a bunch of papers with an oversized magnifying glass.”

After Jayanta Biswas quietly changed the overspilling Bournvita into aamchi Mumbai’s cutting chai, and we (me fueled by Anirban Choudhury’s eye for the detail) both agreed on the shadow speed of the text bubble/ ribbon and the glittering celestial objects on the cover, I remembered the requirement of that expensive piece of retail space for displaying the logo of the publisher.

Of course, Redgrab Books, like I suspect not many publishers would, have backed the madness that went beyond ‘Mostly Mundane’ and they fully and any other appropriate adverbially deserved the place in the quietest corner of this raging cover. That they did not leave the back cover to chance or to me

But then, like every good things in life, the cover story also began much before I requested Jayanta to play King Midas. The prompt for the cover came from my significantly better half, Sharmi. Still earlier, the inspiration to create a cover that stands out came from some of the best book covers that I have seen in recent times, designed by the brilliant team at The Book Bakers and the man at the helm of affairs there, India’s best known literary agent these days, Suhail Mathur. Now the world would know who led me to Prayagraj, the home of Redgrab Books.

Coming next: The Mostly Mundane Blurb

Shantilal Biswas, a man with the grace of a bull let loose in a porcelain shop, found himself facing a predicament that could rival a Big Bazaar billing counter queue on a Wednesday. An invitation – actually, more of a summons disguised as an invitation – had landed on his desk, demanding his presence in the obscure village of Muchipara. Now, Shantilal was no stranger to obscure villages; his auditing job required him to visit places where chickens crossed the road with more purpose and dignity than humans. But Muchipara was something else entirely.

“Muchipara,” he’d mumbled to himself, rummaging through his dusty atlas for any hint of this godforsaken place. “Is that even in Bengal? Or have they exiled me to Odisha now?”

As it turned out, Muchipara lurked somewhere in the hinterlands of Bengal, a place where, it seemed, electricity arrived on festival days and mobile network coverage was a rumor peddled by optimistic telecom companies. The purpose of his visit? A benevolent society founded by some long-dead zamindar had misplaced some funds (several lakhs worth, as the whispers went), and Shantilal, bless his pedantic soul, was deemed the only accountant trustworthy enough to unearth them.

“As if I don’t have enough troubles chasing vanishing paise in Calcutta” he grumbled, tucking his prized tiffin carrier and a thermos of scalding chai into his worn briefcase.

The journey was an unmitigated disaster. First, there was the train. Not one of those sleek air-conditioned carriages that Shantilal favored on official trips, but an ancient relic that coughed, wheezed, and threatened to derail at every bend. Squashed between a snoring goat herder and a woman with suspiciously pungent pickles, he endured a symphony of snores, bleats, and stomach rumbles. Then came the bus – a ramshackle contraption that defied all known laws of physics and seemed intent on catapulting its passengers into the nearest paddy field.

By the time he reached Muchipara, Shantilal was resembling a less-than-pleased thundercloud. The village was small, the kind where the arrival of a stranger was akin to a solar eclipse. Children peered at him from behind mud walls, dogs barked with alarming enthusiasm, and ancient grandmothers paused their gossip sessions to assess the new spectacle.

He was led to the ancestral home of the zamindar, now converted into the society’s headquarters – a rambling mansion with peeling paint, cobweb-festooned ceilings, and a faint aroma that Shantilal could only attribute to a possible bat infestation. He was greeted by a committee of village elders who seemed to speak a dialect of Bengali only distantly related to the one Shantilal knew. After much bowing, gesticulating, and liberal sprinkling of broken Hindi, he was shown to his room.

It was a chamber of horrors. The bed resembled a medieval torture device, the single window was protected by a rusty mosquito net that looked like it had survived a war, and the solitary lightbulb flickered with a menace that suggested an imminent demise. Shantilal, never known for his stoicism, felt a surge of panic that was not entirely due to the potential insect onslaught.

“Where is the attached bathroom?” he’d demanded, aghast. He had the bladder the size of a pea and was accustomed to civilized plumbing.

More gesticulating, more broken Hindi, and then a revelation that made him want to hop right back on the death-trap bus and return to Calcutta. The bathroom facilities involved a brisk walk to a nearby pond and the dubious privacy of a strategically placed bush. Shantilal’s urban sensibilities reeled in horror.

Dinner was an experience designed to test both his fortitude and his intestines. Curries of unidentifiable ingredients blazed a fiery trail through his system, making him acutely aware of the lack of indoor plumbing. And as the mosquito legions launched their nightly offensive, he discovered that, horror of horrors, he’d forgotten his mosquito coil. Shantilal retired to his torture-bed, slapping ineffectually at the buzzing hordes and cursing the day he’d decided to become an accountant.

The next morning, armed with his ledgers, a fistful of antacids, and grim determination, Shantilal plunged into the investigation. The society’s accounts were a nightmare that would send lesser accountants into paroxysms of despair. Ledgers were missing, receipts were written on scraps of what may have once been banana leaves, and the concept of financial organization seemed as foreign to the committee members as quantum physics.

As days turned into a bewildered blur, Shantilal developed a survival routine. He learned to navigate the treacherous pond-and-bush situation with the steely focus of a commando. He discovered that liberal doses of fiery tea could temporarily quell the volcanic rumblings in his stomach, although their effect on his bladder was questionable. Most importantly, he developed an unlikely friendship with the village postman, a spindly man named Haripada with a fondness for cryptic proverbs and even more cryptic paan stains.

Haripada, bemused by this flustered city-dweller, became Shantilal’s lifeline. He translated the committee’s indecipherable Bengali into something Shantilal could grapple with, procured life-saving mosquito coils, and even introduced him to the culinary salvation that was dim-bhaja (simple, fluffy egg omelets). Turns out, Muchipara had its own strange charms.

Still, the investigation was an uphill battle against both the committee’s chaotic bookkeeping and Shantilal’s rapidly fraying temper.

“Where is the entry for the year the school roof was built?” he’d bellowed, his usually meek voice rising in exasperation one morning. “There must have been a bill from the contractor!”

The committee members blinked, shuffling their feet uneasily. One of them coughed and finally ventured, “Sir, that year, there was a good monsoon. The bamboo for the roof… it grew in our own forest…”

Shantilal stared. “And the labour?”

“Our villagers, Sir. They built it. Community effort.”

Community effort, indeed. His accountant’s heart wept at the blatant disregard for financial protocols. How was he supposed to track expenses that seemingly materialized out of thin air?

One sweltering afternoon, frustration drove him out of the musty mansion and into the village. Shantilal, normally a creature averse to any exertion more strenuous than flipping ledger pages, found himself wandering. Children, finally accustomed to his strange presence, giggled and chased him, trying to poke his generous belly. Beneath a banyan tree, a group of women washed clothes in the pond, their laughter pealing through the air. In a sun-drenched courtyard, an ancient man sat, weaving an impossibly intricate bamboo basket.

And then he saw the school.

It was a small, brick structure, sturdy and modest. Children’s voices drifted out of the open windows, a mishmash of recitation and barely contained chatter. Suddenly, Shantilal understood. The missing ledgers, the seemingly vanished funds – they weren’t lost due to corruption or even incompetence. They were here – in the bricks of the school, the laughter of the children, the intricate weave of the old man’s basket. Muchipara’s currency wasn’t just rupees; it was in bamboo from their forests, in the labour of their hands, in the very fabric of their community.

The revelation hit him with the force of one of Muchipara’s fiery curries. Of course! The problem wasn’t a lack of accountability, it was his way of measuring it.

Back in the mansion-turned-office, Shantilal laid out his new plan. There would still be ledgers, of course. He was an accountant, not a revolutionary. But alongside the entries for building materials and contractor fees, there would be columns for the number of bamboo poles harvested, the donated man-hours, the value of the home-grown vegetables that fed the workers. His ledgers wouldn’t just track money; they would track the heart and soul of Muchipara.

The committee members were hesitant at first. Such a system was unheard of! But Shantilal, emboldened by a newfound respect (and possibly a touch of fondness) for this off-kilter village, persisted. Slowly, meticulously, he translated community spirit into numbers and columns.

(‘Mostly Mundane’ is my upcoming book on the exploits of Shantilal. This story predates all other featuring in the book and is not included. If you find this one to be agreeable to your taste, please let me know on WhatsApp @ +919870071069).

“Tatha always complains that my cases revolve around individuals of overseas origins. It’s high time I break the myth,” Sutanu said, taking a sip of black coffee from his black mug. Our meets had become an early casualty of the series of lockdowns. After shifting the goalpost twice, we were facing each other the first time over Zoom, agreeing to discuss everything except COVID. There was another difference, though. Two more of our M. Com. batch mates had connected for the session- Promit Ray, the seasoned bureaucrat in the West Bengal Government and Aliya, one of the few entrepreneurs our batch has produced.

“Go ahead, I have only written what I have seen,” I kept the disclaimer short lest it changed the course of the chat. Promit and Aliya too joined in, asking Sutanu to proceed.

“Well, all of you might remember the news from 2016. The death of Wahid Mahajan in a crossfire at Jhargram.”

“Yes, I thought there were many a question left unanswered there,” Aliya sounded skeptical.

“True, I mean the way the media had made it look, anybody would have questioned the validity of the claims made by police, but a later investigation could not prove any foul play, so I will leave it at that. Today, I am only going to tell you how and why we apprehended Wahid,” Sutanu continued in his characteristic calm.

“Inspector Arnab Joardar had undergone induction with me. In the spate of transfers between the Kolkata and the West Bengal Police in 2014, he found himself transported to West Midnapore while I somehow survived to continue at the Homicide Squad. When I got the call from Arnab that evening, he was in a dilemma.

He had returned late the previous night from a week-long vacation with his family in Kolkata. After a quick nap, as he was getting ready to resume duty, the call came from one of the ASIs of his station. The police had recovered the body of an unknown 25-year-old lady from a high drain behind the house of Sekh Lallan of Kuila village early morning. Since Arnab had arrived late, the Circle Inspector had asked others not to bother him till nine and had himself left for Kuila. By the time Arnab could join him at ten, they had already dispatched the body to Jhargram for postmortem. A boy, while defecating in the open field beside the Sekh residence, had seen the couple dumping the body into the drain, but kept mum. By the time there was enough sunlight for everybody in the neighbourhood to notice the dead woman, Lallan was gone from the village. The police believed that someone had strangled the victim with a gamchha that was left attached to her neck.

Police took Shefali, Lallan’s wife and alleged accomplice in the murder, along with seven others, into custody. CI Mr. Bhanja had, before leaving for the Headquarters, asked Arnab to lodge a case against Lallan and Shefali. But, as Arnab continued with the oral enquiry with the other villagers, an important information had emerged.

It was the truth that Lallan had several pending cases of kidnapping, extortion, and sexual abuse against him. But Rustam Hussain was no different. A long-standing adversary of the Sekhs who would stop at nothing to score a point against Lallan, Rustam was also on the run.

“Is that why your friend, this Inspector Joardar, was in a dilemma?” Promit asked as Sutanu had stopped for another sip.

“That had made Arnab curious, but he was still not suspecting Rustam. He was more concerned with the bigger picture- the reason that he got me involved in the case.”

“The bigger picture?” I lacked in restraining my curiosity.

“Yes, Arnab remembered that in the six months before the Kuila incident, individuals had discovered three other bodies dumped at different locations in the district.”

“A serial killer?” it was Aliya’s turn to pop the question.

“And Sutanu will tell you why the killer is not to be one. Let’s hear it out,” I told from my experience involving a murderous jockey and his cousin that Sutanu had solved in his last few days with the Homicide Squad.

“Arnab had suspected that. Presence of a serial killer in the district is not unheard of, but the Police there, especially at the ground level, had little or no acumen for dealing with such a criminal mind. If Arnab was right, our support could have become critical. He had another reason to believe that Lallan was not the perpetrator. He was way too smart to dump the body at his own backyard if he had committed the murder.

I told Arnab to talk to the SP to buy some time before lodging the case against the Sekh couple. I knew the young IPS Anand Trivedi, a protégé of our Commissioner, who had till the last month been SP, CID. The familiarity gave me confidence that he would understand what Arnab had to say. Half an hour later, Arnab again called to tell that he had got time till that night to come up with any other lead. There was another development. An inexpensive mobile device, which was found lying beside the body, had become drenched and malfunctioned. After hours of trying, the Binpur Police had activated the phone. The call history had one number marked as “Abbu”. Arnab had called the number from the girls’ mobile. The respondent had identified himself as the father of Fatiha Alam, the girl to whom the mobile belonged. He said he was a resident of Bankura while Fatiha worked in Kolkata at a tailoring unit. Arnab told the man Ghazi that the girl had met with an accident and was getting treated at Binpur Health Centre. Ghazi had said he would start for Binpur. Arnab was expecting him to reach before the light dies for the day.

‘That’s at least four hours from now. Do you have the coordinates of the tailoring unit that Fatiha works for?’ I asked him. You can call it superstition, but until Ghazi identified the body as that of his daughter, I couldn’t mention her in the past tense.” Sutanu said.

“Was the body not Fatiha’s?” Aliya’s mind raced with anticipation as she sought answers.

“Please hold your horses. Arnab did not have the location for her workplace, but Ghazi had given him a Kolkata landline number of the business. He could have called them, but wanted to know if I could chip in with a visit to the workshop.”

“And you agreed?” Promit asked.

“Yes, I had little on my desk, and Arnab had only a few hours left before his deadline. I had to act fast. The directory search for the landline number had led us to the Kasba address of Istanbul Garments. It turned out to be a single-storied house with a signboard outside displaying the name of the organization in white calligraphic lettering against a bright red background. A small verandah led to the small but swanky reception. Both me and Rajesh, an ASI were in plain clothes, but the way the girl at the reception stood up and greeted us had made it clear she could see the patrol vehicle we had descended from on the CCTV monitor. It helped in cutting down on formalities.

“That’s Fatiha, b-but is she dead?” Saima, the receptionist, asked in disbelief when she was shown the image of the corpse received on WhatsApp from Arnab.

“Yes. Were you friend with her?”

“Both of us have been working here for the past couple of years, though she was in production. But she did not appear to be sick or anything. How did it happen?”

“Will tell you everything you need to know, but before that, I would like to have some more information. When did Fatiha last attend the workshop?”

“The day before; we were closed yesterday. She had asked for a day’s leave today; said she was to go visit her father in Bankura.”

“So, you did not enquire when she had not turned up for work this morning.”

“That’s right, Sir.”

“Had you noticed anything amiss about her in the recent past?”

“Not really, but Friday afternoon, after Sameer had left, she seemed a little unmindful.”

“Who is this Sameer?”

“Oh, he is a nice guy. Fatiha called him a brother. Of late, he used to pay her a visit here often.”

“By any chance, do you have a contact number of this Sameer?”

“No, I never asked.”

“How does he look?” Rajesh had asked, breaking his silence for the first time.

“I think we need not ask for a description; don’t you have the CCTV recordings from last Friday, Saima?” I quipped.

It was Rajesh again who spoke first while we were going through the footage.

“That’s Wahid!” He exclaimed.

“No, that is Sameer,” Saima said, oblivious to the notices that all Police Stations in our state adorned a few years ago featuring the mugshot of Wahid Mahajan. Rajesh and I exchanged glances. We were thinking about the same line. Arnab appeared to be right in not registering a case against Lallan and his wife. Even with the staggering number of alleged hits to his name, Wahid was no serial killer. He killed for only one reason-money.

As we boarded our Gypsy with the memory chip containing the CCTV recording secured in an envelope, Rajesh made the call to Tiljala PS. Haranidhi Pal, the station-in-charge confirmed Wahid had not missed on his daily attendance to be recorded at the PS as a part of his parole arrangements in the past fortnight. More importantly, he had not turned up yet at the station on that day. I asked Pal to take Wahid into custody if he made the visit, and our driver to take us to Tiljala.

On our way, I had texted Arnab to bring him up to speed. He called back to report that they had found a lady’s purse with a small diary inside on the asbestos roof of the washroom outside the Sekh residence. Apparently, someone had made the only record in the diary the previous day. “Lallan Sekh has brought me here. I fear for my life.” The handwriting and spelling were too rudimentary for a graduate that Fatiha was. Arnab thought it was a piece of further evidence that someone was trying to frame Lallan.

“‘Drop the name of Sameer to both Shefali and Rustam’s family. Tell them we believe Sameer is the killer, and if they tell the truth, they might walk free soon,’ was my advice for Arnab. It worked. Rumel, Rustam’s unemployed son and Sharmeen, his much older wife admitted that Sameer and Fatiha had spent most of the previous day at their house, had dinner with them. At four in the morning, Sameer had left saying he was to take Fatiha to her fiancé in Jamshedpur. It was an hour later that Shefali recalled discovering the body inside their washroom. She woke Lallan up, and it was a hurried decision for the couple to get rid of Fatiha’s body, not that Shefali knew either the name of the deceased or Sameer.”

“But how was Wahid or Fatiha related to Rumel?” Aliya wondered.

“Good question and Arnab too had asked the same. Rumel said his cousin Sagir had requested Sharmeen, the lady of the house, to accommodate the “siblings” for a day. It did not appear that Rumel was lying, and Sagir was not one among the arrested. Sagir Ali was a Kolkata resident. Again no address, but his mobile number was active till the wee hours of the day, somewhere in Rajabazar. I don’t want to bore you with the details but, in the next few hours, Ghazi had identified the corpse to be of his daughter, a case of conspiracy to murder against Rustam and his family and another for an attempt to destroy the evidence against Lallan and Shefali were recorded by Binpur Police, and an unsuspecting Wahid was put into the Tiljala PS lock up. Sagir was yet to be apprehended. Any question?”

“You mentioned Sameer had told Rumel they were going to meet Fatiha’s fiancé. Does that have anything to do with the case?” I asked, in desperation to find a twist in the tale.

“There you are my storyteller friend. The fiancé, as we would later find out, was Babul Islam, a Jamshedpur-based entrepreneur. The only problem with the match was Babul already had a wife in Sofia Mahajan, Wahid’s sister. When Sagir had contracted the hitman for a dead body to be planted at Lallan’s residence, Wahid had seen in the assignment an opportunity to translate his effort to save the marriage of his sister into a profitable venture. He knew about the three murders in the district and used the gamchha to wring the life out of Fatiha’s body to make it look like the doing of a suspected serial killer on the prowl. Sagir did not have the stomach for third-degree, and Wahid was prompt to confess once the news of his employer’s arrest reached him.”

“Tatha might be satisfied with the hurried conclusion, but I still insist on knowing the truth about that crossfire.” Promit sounded like a demanding bureaucrat determined to make the life of his subordinates difficult.

“Well, the goons who had intercepted the Jhargram Police van carrying Wahid to Kuila for reconstructing the crime scene were not there to rescue him. It later came to light that a Babul Islam of Jamshedpur paid them a lakh to put a bullet inside Wahid’s head. Revenge is far more unpredictable than a staged crossfire, my friends,” Sutanu concluded.

(Based on true events in another country)

Malgudi, bathed in the laziness of a humid afternoon, thrummed with the cicadas’ incessant song. Venkatrao, draped in a threadbare dhoti that clung damply to his limbs, sat with his forehead creased against the rough grain of a wooden bench. In his right hand, he gingerly fingered a crumpled rupee note, its crispness an affront to the sun-bleached monotony of his life.

The money sat heavy, a lodestone attracting a swarm of justifications. It wasn’t a stolen windfall, no sir. Merely a misplaced offering, a stray feather from the temple goddess draped upon his humble doorstep by a careless crow. A celestial nudge, surely, not a temptation.

Venkatrao, a man of modest needs and even more modest means, had dreamt of this note’s possibilities. A fragrant cup of filter coffee at Supposedly Coffee House, the clink of its stainless steel tumbler a symphony against the mundane clatter of his existence. Perhaps even a single, plump samosa, its oily heart bursting with spiced potatoes – a forbidden luxury.

His wife, Saraswati, stirred within him like a reproachful ghee lamp. Her bony fingers, etched with the maps of their shared austerity, would count the wrinkles on the note with disapproval. Her tongue, sharp as a curry leaf, would dissect his flimsy justifications, leaving him stripped bare in the sun-drenched courtyard.

Yet, the note persisted, whispering of possibilities. Venkatrao could almost smell the coffee, its bitter aroma weaving through the dust. He could taste the crispness of the samosa, feel its greasy warmth slide down his throat. A shiver of longing danced down his spine, a rebellion against the monotonous thrum of the cicadas.

He reasoned with himself, the arguments tumbling forth like poorly stacked mangoes. It was a loan, he’d convince Saraswati. A temporary indulgence, to be repaid with the next meager pay from the mill. Besides, wasn’t happiness a right, even for a threadbare soul like him?

As the sun dipped towards the mango trees, casting long shadows across the dusty lanes, Venkatrao’s resolve began to fray. The note crumpled in his fist, a talisman against the gnawing guilt. He rose, his dhoti flapping like a moth’s wings, and took a tentative step towards Supposedly Coffee House.

But just as he crossed the threshold, a small hand slipped into his. His daughter, Lakshmi, eyes wide and hopeful, looked up at him. “Papa,” she chirped, “Can we buy jalebis today?”

The question, innocent and pure, shattered the mirage of his justifications. Venkatrao looked at the crumpled note, the samosa and the coffee dissolving into smoke before him. In his daughter’s eyes, he saw not just hunger, but trust, an anchor in the turbulent sea of his desires.

With a sigh, he crumpled the note further and tucked it back into his pocket. This loan, he knew, would have to wait. Happiness, he realised, wasn’t just a cup of coffee, but the shared sweetness of a jalebi with his little girl. And as they walked towards the jalebi vendor, the cicadas seemed to sing a different tune, one of contentment and simple joys, sweeter than any stolen sip of coffee.

Thus, Venkatrao returned home, the rupee note a reminder of his victory over temptation, a silent pact with the goddess and his own conscience. The samosa remained a dream, the coffee a distant aroma, but in his daughter’s smile, he tasted a sweetness that lingered long after the jalebis had vanished. And the cicadas, finally, seemed to sing in perfect harmony with the quiet contentment of his heart.

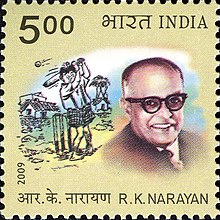

(The third in my series of pastiche is dedicated to none other than R.K. Narayan)

It all began, as these pickles invariably do, with a spot of bother with Aunt Agatha. You see, the annual Ganymede Club bake-off loomed upon the horizon, casting a shadow of trepidation upon the normally sun-dappled brow of my esteemed chum, Bingo Little. This year, Aunt Agatha, a woman with a pastry pan for a heart and a rolling pin for a soul, had devised a particularly fiendish pie. A Moroccan Apricot Surprise, she called it, positively brimming with saffron, cardamom, and enough chili peppers to send a battalion of Cossacks into a tango.

Now, Bingo, like myself, wouldn’t know a cardamom pod from a cricket bat, but when Aunt Agatha, eyes glinting like a magpie in a chutney jar, declared his entry vital to Ganymede Club glory, he was putty in her flour-dusted hands. And so, I found myself enlisted as his culinary co-pilot, navigating the treacherous shoals of this gastronomical Everest.

The baking commenced in a flurry of whisking and rolling, with Agatha barking orders like a Sergeant-Major on a sugar high. Eventually, the pie emerged from the oven, a golden behemoth wreathed in a fragrant cloud that made my eyebrows do the Charleston. “Voila!” declared Agatha, puffing out her chest like a pouter pigeon. “One bite of this, darling Bingo, and the Ganymede trophy is as good as ours!”

Bingo, bless his cotton socks, was never one to disappoint an expectant relative, especially one armed with a rolling pin. He sliced the pie with the reverence of a surgeon dissecting a priceless truffle, and popped a generous wedge into his eager gob.

For a moment, he chewed in contemplative silence. Then, his eyes bulged like poached gooseberries. A strangled gurgle escaped his lips, followed by a cough that would have cleared a fogbank off the Thames. His face contorted, turning the colour of a prize beetroot, and sweat beaded on his brow like diamonds on a duchess’s décolletage.

“Agatha, my good woman!” I cried, leaping up as he clutched his throat with the air of a man being strangled by a boa constrictor with a particularly spicy temper. “What, in the name of all that is holy, have you put in this monstrosity?”

“Why, just a dash of my secret chili paste, darling,” chirped Agatha, oblivious to the inferno raging within Bingo. “Gives it a bit of a kick, you know.”

Kick? This thing wasn’t kicking, it was doing the Highland Fling in a volcano! Bingo, meanwhile, was gurgling like a drain, his eyes watering like a tap left on in a monsoon. I rushed to his side, visions of St John’s Ambulance sirens flitting through my mind.

“Don’t panic, old bean!” I cried, desperately fanning him with a tea towel. “There must be something we can do!”

Just then, inspiration struck me like a custard pie to the kisser. “Milk, Bingo! Milk! Drown the fire!”

With the grace of a hippopotamus on roller skates, I dashed to the fridge and poured a gallon of the white stuff down Bingo’s protesting throat. It was like throwing petrol on a bonfire, but in reverse, I hoped. Miraculously, it worked. The flames in Bingo’s eyes subsided, replaced by a watery gleam of relief.

“By Jove, Bertie,” he gasped, wiping his brow with a trembling hand. “You saved me from a fate worse than Aunt Mildred’s fruitcake!”

The Moroccan Apricot Surprise, alas, never saw the light of the Ganymede bake-off. But that night, over a soothing cup of chamomile tea, Bingo and I vowed never to trust Agatha’s “secret ingredients” again. And as for me, I’ll stick to my tried-and-true jam sandwiches – at least I know what’s in those. After all, one can never be too careful when it comes to the culinary creations of our dear aunts. You never know what fiery surprises might be lurking beneath that golden crust.

(The above piece is the second pastiche I have ever tried, imitating the inimitable P. G. Wodehouse.)